My father in law and my father, an orthodontist and dentist, had careers in “practices.” Those linear career paths, where the job content is relatively invariant despite increasing experience and seniority, are characterized as the practice of the art. “Practice” is the operative word in any role that requires improving skills in a variety of contexts.

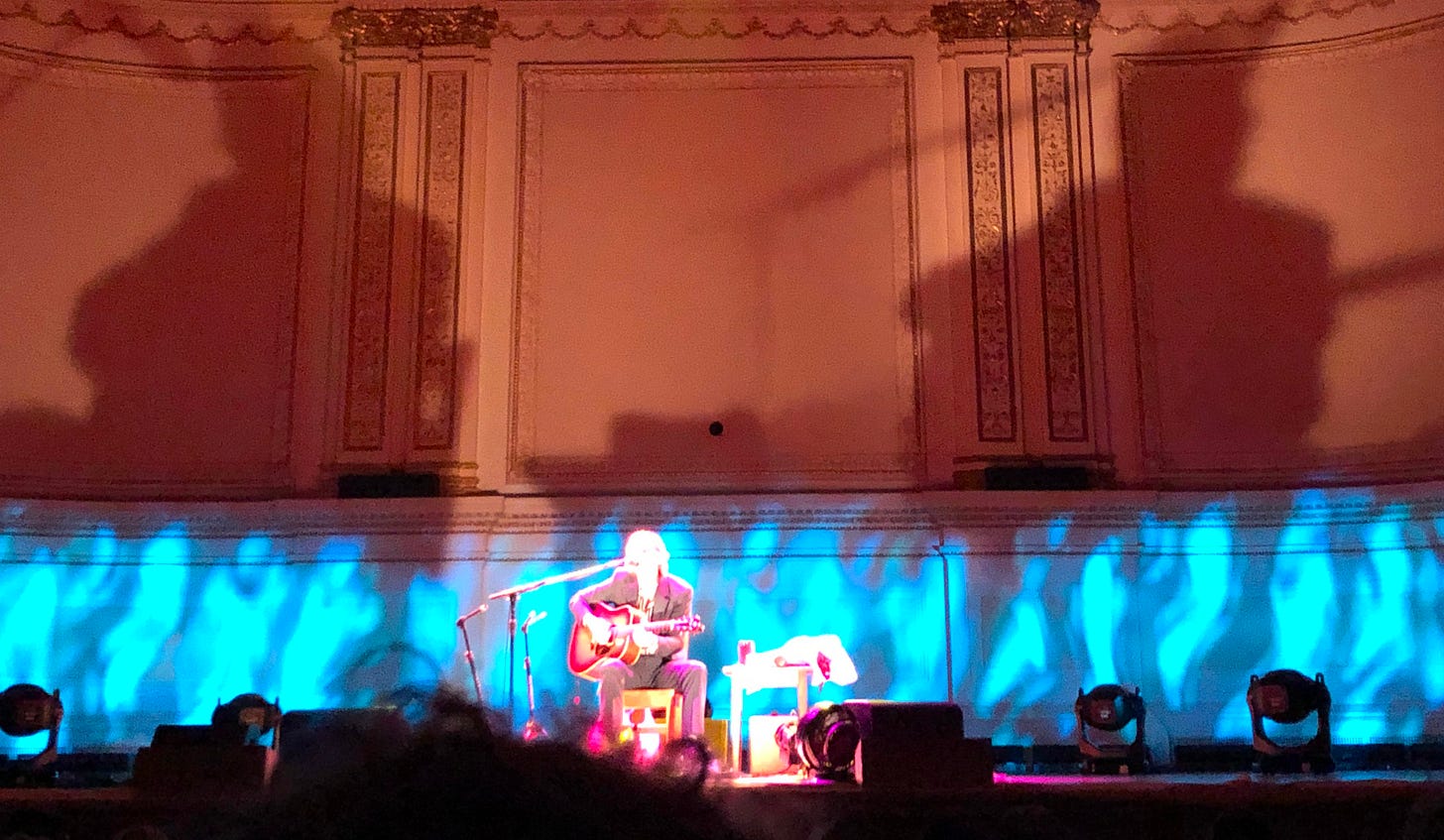

Musicians and athletes separate “practice” from “playing” actual events, such that practice is a safe space to work on individual or group competencies, break down complexity, and repeat in a low-cost failure mode. The old joke for budding musicians is “How do you get to Carnegie Hall?” “Practice, practice, practice” is the geographically independent punchline.

During my career in technology sales many people asked how I developed my public speaking skills. The practice was rooted in years of being a college radio DJ, where you had to plan out a break between songs and commercials, conveying the right headline information and then sending the listener off hoping they’d return to the same spot on the dial. My sole attempt at broadcasting a basketball game clearly showed the value of practice as I ran out of color commentary about six plays into the game, not having built a set of statistics, personal reflections, and player trivia patterns upon which to draw during the nearly fifty speaking opportunities in a forty-minute game.

My current bass teacher emphasizes the value of having a practice plan and notebook. Each week I decide what I’m going to work on, whether it’s learning a song along with a slowed-down Youtube video, working on syncopated rhythms with the drum machine, or drilling scales up and down the fretboard until I’m comfortable finding the notes without looking down — very similar to learning touch typing. The net benefit is literal muscle memory for translating a pattern I want to hear (off beat hits, walking scales to move between keys) into actual notes.

Why don’t we “practice” our technical architecture skills? Anyone who codes in hobbyist or experimenter mode is practicing, but the complex, multi-party design patterns frequently get short shrift in the enterprise. As a result, when we make large system design decisions — often for the first time in the domain, without a safe space for feedback or deconstructing decisions that were not fully informed — we do so from a position of risk avoidance as opposed to calculated risk management.

O’Reilly Media started a practice called “Architectural Katas” — named for the form repetition in martial arts training to teach muscle memory in a safe, non-combative space — that allow you to build multiple teams to build varied and varying views of the same design problem, share their review and learn from the process. It’s a powerful way to develop architectural skills without the weight of a multi-million dollar vendor contract raising the risk aversion to complex design.

Christopher Alexander’s “A Pattern Language” is the seminal work exploring how complex domains develop their own language and abstract patterns. Rooted in civil engineering and urban planning, it is the source material for “city planning” enterprise architecture disciplines. Identifying patterns — whether it’s defensive coverage in the NFL, complex polyrhythms in progressive rock, or a rate-limiting transactional scale database construct — requires practice where mistakes can be analyzed and corrected, not fed forward to your performance review.

Practice any art, music, singing, dancing, acting, drawing, painting, sculpting, poetry, fiction, essays, reportage, no matter how well or badly, not to get money and fame, but to experience becoming, to find out what's inside you, to make your soul grow. —Kurt Vonnegut

The practice of computer science is many things - mathematics, logic, creative writing and an art. An interviewer once told me “Good code sings off the page.” We should practice to further develop the practices of scale, user experience, anti-fragility and community led development.

Grace Notes:

I’ve restarted my Amazon Associates account to collect a small commission when any reader clicks through (and buys via) a media link. The official notice and disclaimer is “As an Amazon Associate I earn from qualifying purchases.”

Christopher Alexander’s “A Pattern Language” is back in print and also available in a Kindle version. It’s long, but like a Neal Stephenson book you’ll appreciate the mental heft as well. It has informed much of my thinking about city planning and technology.

Seems the Kevin Kelly “1,000 True Fans” idea is also having a bit of a nerdy renaissance; DGM Live (who promote the King Crimson and related catalogs) started their own 1000 Club.

Many of my ideas about musical practice stem from conversations with Natalie Cressman and Markus Reuter. They are as diverse as my reading interests; Natalie plays trombone and has a soulful voice, both of which have toured with the Trey Anastasio Band, Phil Lesh and Friends, Oteil and Friends, the Motet and others. Markus is one-third of Stickmen with Tony Levin and Pat Mastelotto, a pioneer in the touch guitar playing and luthier space, and my current reigning space-time champion of polyrhythms. Both have deep Bandcamp catalogs and merch; they both rely on direct sales to fill in when touring is light (as it frequently is during the winter months).

Currently reading: “A Conventional Boy,” by Charles Stross, re-entering the Laundry Series in a delightful way.

Listening while writing: “Blue Rondo A La Turk” by Dave Brubeck, “Parallels” by Yes (the Yesshows version, trying to learn the bass line underneath’s Steve Howe’s outro solo) and Dead & Company “Eyes of the World” (7-1-23 Oracle Park version, Oteil Burbridge’s bass lines are the perfect blend of jazz, blues, jammy prog and Phil Lesh’s originals).

I have been preaching Kevin Kelly's 1000 True Fans mantra to all the artists I support on Patreon. Jack Conte, CEO of Patreon as well. IT's more than simple math - it's the idea that we can crowdfund the art that we want rather than that the corporations wants. It gives alternative creativity a chance to breathe.