Money tells a story. Since the first coins were minted by hand, icons on our money convey political, social and long-term commentary. I’ve been a sometimes numismatic nerd since being handed a box of coins representing decades of family members’ travails and travels: Uncles going through Europe during the World Wars; family members leaving Russia (now Ukraine); circulating US coins that found their way to my grandfather’s general store and may have spent a decade or more in the small safe under the cashier’s feet.

Before mass communications, coins were equal parts propaganda and purchasing power; they carried pictures of the emperor, the king, or the revolutionary minting authority. Today’s circulating coins highlight our history as well as our current emphasis; Italy’s commemorative 2 Euro coin simply thanks healthcare workers, masks replacing the Phrygian cap as a bold sign of empowerment.

“Money is propaganda” – Dave Hendin, Biblical coin expert

I’m going to talk about the velocity of money in two parts - here in personal terms, moving from the coinage that flowed through Grandpa’s store to my fanboy fascination with Kiva; on the paid subscription side (nudge) looking at how corporate technology funding conveys an equally indirect story of importance and engagement.

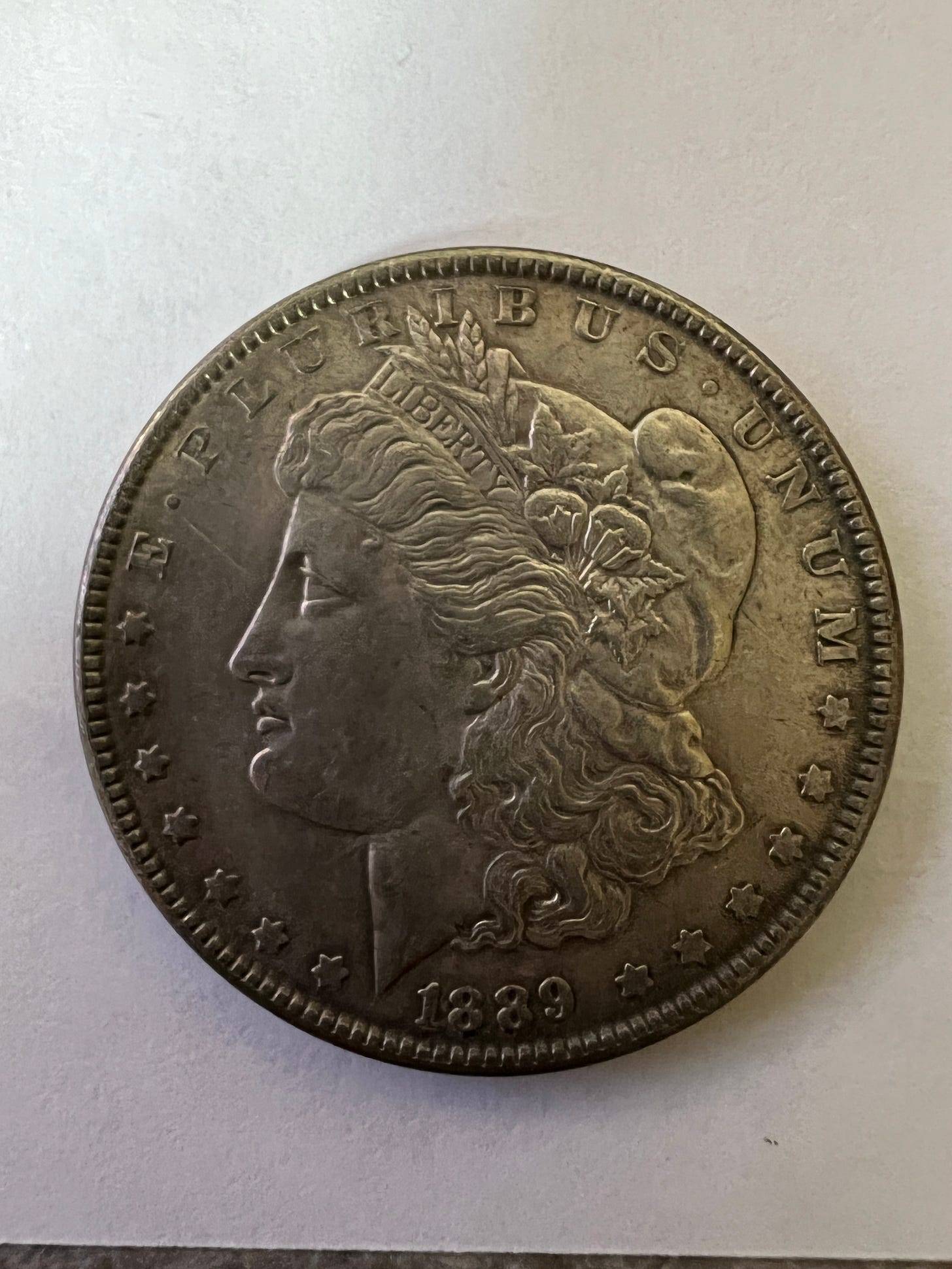

My main interests are the current US quarter series, late 19th century silver coins, and biblical era bronze coins. circulating quarters to fill in my Jeopardy-level knowledge of the United States, from state iconography to National Parks. Silver coins from the late 19th century tell the story of the American West - the new mint springing up in Carson City to make the Comstock Lode fungible, trade dollars (the largest coins ever minted) to normalize the exchange mechanism with growing Chinese trade partners. Morgan dollars and Liberty quarters paid for gas, sandwiches, and hardware in Grandpa’s store, and I often wonder about the very personal stories of those who traded silver for a literal slice of life in that store. I discovered everything about the Carson City mint in the age of Google searching as nothing with a “CC” mint mark made it far enough east in the decades the store was open and silver coins literally outweighed paper money as payment.

This bronze coin dates to the year 132 AD, or as it’s minted “Year One” of the Jewish Revolution against the Roman Legions holding Jerusalem, sixty years after the fall of the city. Many coins of that era were overstruck Roman army coins, fomenting revolution and dissent; the images on obverse and reverse represent the marks of the land - a lyre, a date palm - as well as the 7-armed candelabra that today is the national symbol of the State of Israel.

I was equally fascinated by the late Neil Peart’s National Park passport stories in “Ghost Rider,” and pulling the representative quarters from my morning bagel change lets me tour the country vicariously from the safe position filling a Whitman folder. Before mass communications, coins were equal parts propaganda and purchasing power; they carried pictures of the emperor, the king, or the revolutionary minting authority; today they reflect states rights in iconography. You instantly absorb national culture by looking at money - pictures, places and denominations. I once navigated to my Merck Prague office with a non-English speaking driver using the limited vocabulary from a 200 koruna note – a measure in meters and the word for brewery sufficed to land me within walking distance.

As money became increasingly abstract - checks, then electronic payments and socially accessible vehicles like PayPal - it lost some of its narrative power. Velocity increased, as social impact and portent decreased, and coins were relegated to the recesses of eBay auctions with the Beanie Babies and other somewhat quaint hobby interests. Venmo reignites a social aspect to money, but it’s more telling our story through spending rather than a proclamation about our national interests. Look at my dinner bill, not the face on the bill used to cover.

The confluence of money’s narrative carrying capacity and the socialization of access fine-grained money transfers led to a personalization of its story. It’s no longer the emperor or king or revolutionary hero stamped into the planchet; it’s the small dry goods store owner in Rwanda or the farming collective in Guatemala that benefits from microloans through non-government lenders backed by aggregating sites like kiva.org. The ability to offer credit on a small scale brings the story of money full circle: my grandfather made a book of credit, although he rarely consulted it as small losses were acceptable in his small community. Silver coins in that under floor safe have stored that are foils to the payments never received, except in goodwill created. Money tells the story we want and need, if we combine our current tools and vehicles to direct it.

Words: “The International Bank of Bob” is a tremendous introduction to Kiva, and part of my inspiration for sharing the very personal nature of small scale loans in my family. I’m also reading Susan (Fowler) Rigetti’s newsletter and her first novel “Cover Story.”

Notes: I wrote this over the course of several months, and my backlog of musical notes tells a separate story of inspiration. Van Morrison’s “Moondance,” especially “Into the Mystic” and its opening line of “we were borne before the wind.” I prefer that homonym, as I think of the song as carrying us somewhere – like a nice cash float. Weather Report’s “Legendary Concert” re-release of their Tokyo tour, and most recently the last few Trey Anastasio Band shows from Atlanta and Boston.