A central part of leading engineering teams is developing talent and creating opportunities for career development. “How do I get promoted” is far too blunt; it assumes you are climbing the corporate ladder in competition with your peers. “How do I develop a career path” is the better view, as it puts the onus on the employee to create a set of career arcs. You can either have a closed career arc, where you are looking up into an organization hierarchy with ever-narrowing layers, or a open one in which you are always at the bottom of an expanding funnel.

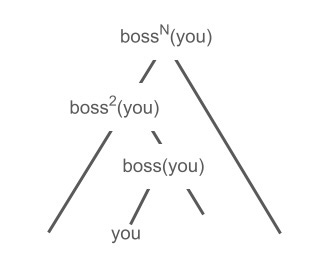

The Caret: Moving Up The Org Chart

The downside to this career arc is that it’s not an arc — it’s a series of steps up a ladder where each step is more complex with competition (internal and external) and may or may not afford the best use of your skills. If you’re one level from the top, then it’s normal to discuss succession planning and how you can be considered for your boss’s job; if you’re three levels down in the organization aspiring to lead the organization is admirable but also assumes that the skills, organization and goals involved are somewhat invariant over that period of time. Usually, they’re not. Further, if all of your peers are roughly the same level think the same way, you’re constantly in a Hunger Games competitive mode. In an organization of 100 people, there’s only one root of the tree and over time the odds are not ever in your favor.

The Open Funnel: Create Your Own Corporate Adventure

I prefer to think of career planning as starting with an individual at a point in time, with a set of skills, goals, and interests. This puts you at the bottom of an open funnel.

The next phase of career planning is to pick a number of target roles two jobs down (or up) the line: if you’re a manager these might be VP level roles; if you’re a VP these can be executive management or larger roles in other organizations; if you’re an individual contributor then it’s either a management role or a staff/principal level position. The inversion of the classic organization chart shifts the conversation from “How do I get promoted?” to “Where would I like to go?”

The second crucial attribute of starting with Role + 2 is that it opens up possibilities in other companies, in other industries, and in parallel organizations. Yes, there’s more competition for those roles, but you also increase the number of targets within sight. Mapping your skills, interests and experiences into this future-you state allows you to think about lateral skills translation (what problems are in the same equivalence class as ones you’ve solved or addressed?) and creative application of your interests and ideas to new domains. One of the reasons I was able to move from a networking technology company that made routers and switches to a pharmaceutical company that designed oncology therapies is that the data management, scientific and scalable compute, and graph problem experiences translated laterally.

In doing this future state planning you invariably identify gaps: skills, experiences, management scope and execution command that you simply don’t have. Use the gap analysis to map out what you’re looking for in a next role - now the script is flipped from “How do I get promoted” to “What will I get out of a promotion.” Doing so frames your planning for the next role, how you should approach, research and interview for it, as well as again opening up a set of roles that may not be linear progressions in your organization but take you to landing spots rich in institutional knowledge.

You create a portfolio of future roles, each with value conveyed, requirements, and the ability to accelerate you into the next set of portfolio options.

Even at this stage in my career, I maintain a convex map of job ideas: My eventual state involves advisory and board work, music and musician engagement, micro scale financial services and what my friend JSS calls “artisanal computing.” Yes, this is the “retirement portfolio” but starting that process when you are 60 or 50 is far too late. Develop the portfolio thinking — adding, pruning, detecting alignment, networking with experts who offer guidance, direction or advnice — early in your career.

Resources:

I am a huge fan of David Epstein’s book “Range,” and his “Range Widely” Substack newsletter. His particular piece on the value of hobbies cemented my view that having a luthier shop and guitar sound lab might be a useful retirement goal.

Domenica Degrandis wrote “Making Work Visible” which is one of my functional references (short form YouTube video is the SparkNotes version). She explores what steals our time and makes us less productive; if your work suffers from invisibility it is hard to promote your skills and experiences.

I have been listening to, reading about and thinking through the New York City music scene of the late 1970s: Bruce Springsteen coming out of “Darkness,” Talking Heads at their peak, CBGBs in full swing, punk setting one agenda while Robert Fripp and the Roches crossed the streams of prog, folk and rock. On Monday I went to see a full album performance of Fripp’s “Exposure,” with Terre Roche and some of Fripp’s inner circle of chordistes. Highly recommended if you can catch one of the remaining Northeast dates.

As I’m editing this while en route to Phish’s spring 2025 tour, I naturally have improvisation, music and the band top of mind. Amanda Petrusich’s piece in the April 21 New Yorker is simply fabulous in discussing how the band refused to follow the “classic” career arc, and in doing so built an empire — streaming, ticketing, archiving, charitable organizations and a traveling circus of loyal fans — that has powered them for 40 years. They are the anti-Rolling Stones; the convex to the concave.

plans are nice but then recessions happen, and when orgs start doing layoffs annually if not quarterly it's a transition to "survivor," hoping you don't get voted off the island in each round. As opposed to "where you'd like to be in 5 years." Then the valuable skills are 1. getting as close as possible to the dwindling revenue sources, and 2. knowing how to ingratiate yourself to the people making the decisions