My relationship with poetry is odd. As a music lover and off-key vocalist who loves the reverb of a tile shower, I belt out stanzas with the punch intended to a fleeting audience of water droplets. As a reader, though, it’s 98% prose and perhaps 2% picture books. My sole attempt to read poetry dates back over four decades, when I was asked by a much-adored English teacher to pinch hit in a forensics competition; he was down a poetry reader and without a full team the true talents who depended on this last competition of the year faced disqualification. I did what any senioritis-suffering, take one for the English team student would – I read a collection of Yes lyrics to a somewhat stunned group of judges. My junior teammate advanced in competition; I regressed to more sci-fi and a new author called Stephen King.

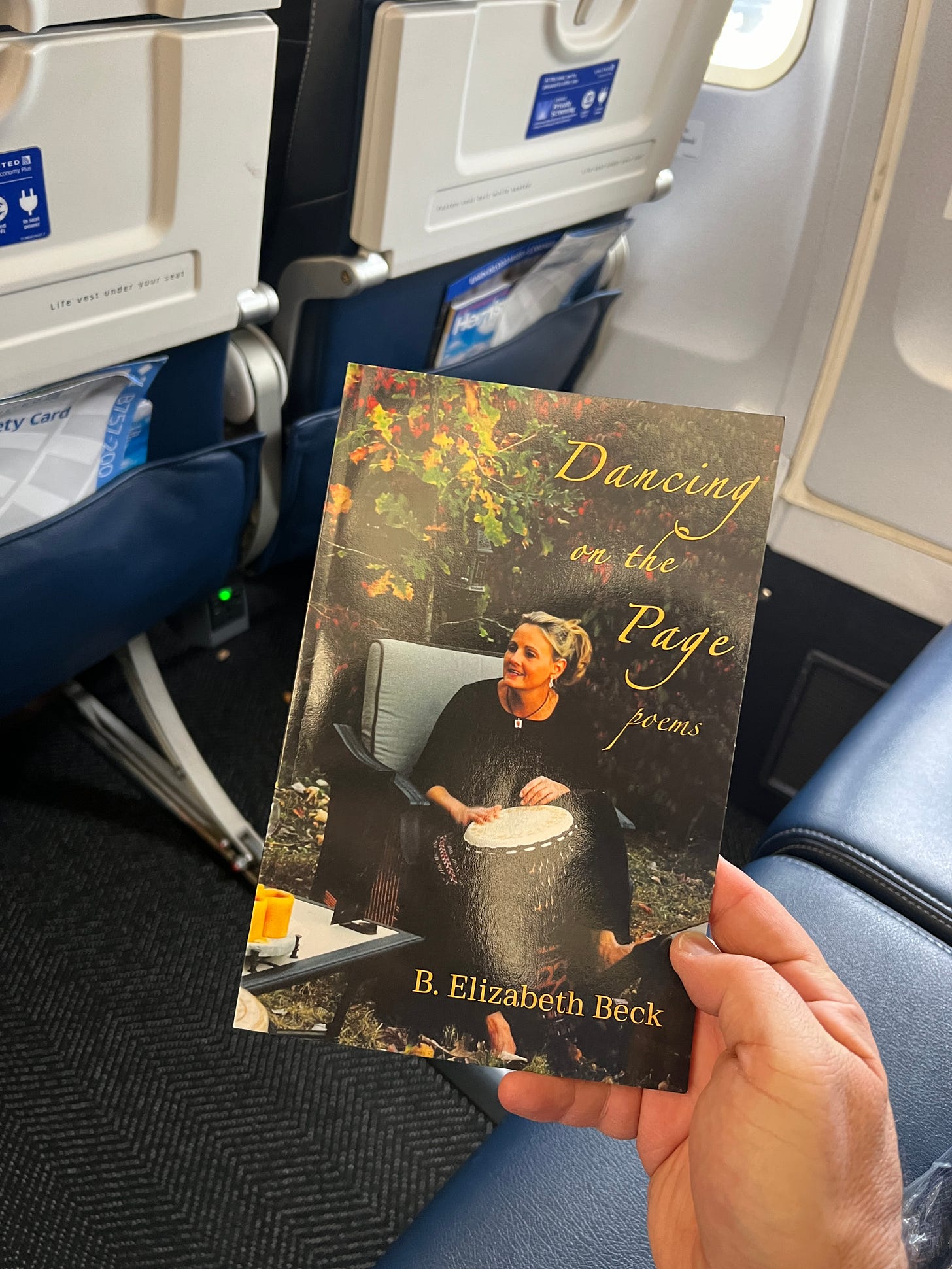

That turned out to be somewhat prescient for learning to enjoy poetry in a different context. I bought B. Elizabeth Beck’s Dancing On The Page at the confluence of three events: I’m sharing the poster gallery with her next weekend at the Phish Studies 2.0 conference, I thoroughly enjoyed her Phish-tinted “Summer Tour” trilogy, and her poems about love and loss seemed timely as I continue to process my mother’s death two months ago.

Summer Phish tour reminds me of summers down the Jersey shore: there are recurrent characters, familiar places and flavors, repetition that sets cadence; tour is summer camp or the comfortable worn beach house for adults. Beck’s ability to capture the zeitgeist of those shared moments made me pick up her collection of poems. For an hour, slowly speaking words loudly in my head, I was able to fix that feeling of conveying the cultural and personal value of music across generations. Wrapped around it were the senses of place and wonder, the fixed waypoints whether they be arenas, street food, or the single name friends whose cross product of fame and impact on our sojourns is as large and invariant as that of Madonna, Sting or Bob the grilled cheese guy.

Jeff Tweedy’s How To Write One Song mechanizes the artistic process of effectively writing poetry, finding related words, themes and the written colors to link them. My teenage experience with Yes lyrics was almost the opposite - Jon Anderson’s words fit the music and spirit of the song, a tone poem of syllables, religious icons, the faded snapshot of relationships. Music gives poetry structure through chords; poetry without music relies on my own interpretation of breaks, phrasing and punch.

The subtlest of song lyric references create a frame across which Beck’s words float, transporting me back to playing “Sweet Jane” on a dormitory step or spinning round and round with friends in the pit. Yes, the Velvet Underground, Phish and the Grateful Dead are the bright notes in the minor keys of loss, relationships, and growing older. A friend to whom I sent a copy texted me that it felt “visceral” which was the exact first word I used in writing about it, now pushed down beneath other captured memories.

I read it cover to cover in one sitting, and went back and re-read a few, and there will be two or three more readings as summer tour approaches and I am again searching for the secret chorus of old friendships and new reasons to dance. Around the sad minor notes, the major chords ring out: of music, travel, old friends, the magic half minute between the house lights going down and the stage lights shining on your musical soul.

The thing about reading poetry out loud is that it reminds me of nothing so much as reading prayers, which i well understand as a native Hebrew speaker. Surprisingly, though, (especially as an English major in college) I never made this connection until I read your post. Thank you.