I’ve edited and recycled most of this piece a few times over the last decade. As Memorial Day heralds the end of the academic year and procession of summer months, I think of my middle and high school classmate Steve Voigt, Navy Seal Team 8, killed in action on October 25, 1996. We honor the memory of the men and women who fought in the World Wars, in the Korean and Vietnam wars, and more recently in the Gulf conflicts, and know that our freedom has been protected by Americans in military service 24 hours a day every day in between.

Regularly editing and sharing this story gives me the advantage of adding perspective. Unlike a doctor, nurse, or serviceman, I’ve had very few situations in which someone’s life depended up on me and the careful execution of my role. The severity of failure never registered with me, as an engineer, until 1991 when I was asked to literally hack a device driver for the US Air Force at the outset of the first Gulf War. Pilots’ lives depended upon my ability to make a Sun workstation talk to an aging TEAC floppy drive with flight logistics data. Contributions to the Gulf War segment of Sentinel Byte, made Woodrow Wilson’s call to “the nation’s service” more clear, and somewhat more personal, but still 10,000 abstract miles away. Leaving technology for healthcare in 2013, I found myself in more projects where the outcomes impacted lives, from accelerating the development of a Covid-19 vaccine or building patient care solutions for blood cancers. However, we are typically playing a long game, with the opportunity to turn off the Zoom call or revisit the algorithms when we hit a point of frustration. I’ve become acutely aware of this privilege, and its dichotomy with the daily lives of our men and women in uniform.

One fall a new kid named Steve Voigt showed up in our middle school classes; he had moved from the South and everyone remarked on his gentle accent and more gentle manners. He was a remarkably good kid — good at soccer and basketball and socializing — and post high school graduation enlisted in the Navy. Steve enlisted one month after our graduation.

His courage, mental and physical strength and fortitude were ingredients that made him a member of Seal Team Eight. Serving on the aircraft carrier Enterprise in the Persian Gulf and Indian Ocean, during the first Gulf War and before the tensions of 9/11, his service was alternately intensely boring and life changing.

He wrote in a letter to his sister in 1996:

Breakfast: Forty-five minute wait in line. Every meal is the same. Standing in line sweating. That’s OK, though. There are people in my country who neither know or care that their freedom is being protected at this very moment. That too is OK, because I do know. I’m doing it.

He concludes:

I understand freedom and the sacrifices that have to be made for freedom to be achieved. The life we live at the cost of our military members cannot have a price put on it. If you saw our paychecks, you would understand.

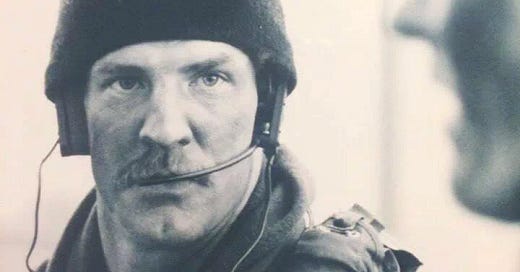

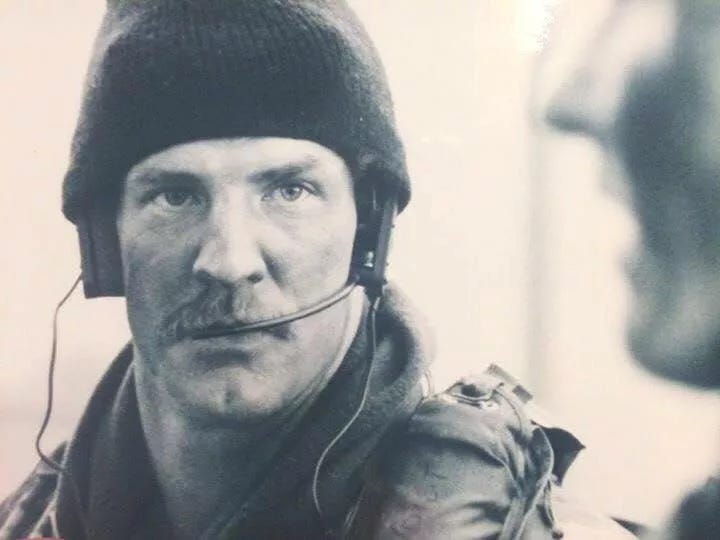

Steve’s entire letter is found at the link, also the source of what I believe to be that last photo of him, above, credit to XY).

He was killed in a search and rescue mission two days later, something I didn’t find out until four years later at a class reunion, and in the 20 years since more details about his service, his commendation and that last letter to his sister have been made public. Steve was, and still is, the only person I know killed in active military service.

Steve’s Navy and Marine Corps Commendation Medal Citation calls out “his ability to motivate his teammates.” While he was an outstanding athlete, he was also a great teammate to the awkward, incredibly poorly coordinated kid on the middle school recreation basketball team (me), and I had the honor of experiencing what would become his outstanding call to personal leadership when I was still a tween. He encouraged me to be better, without picking on me for lowering the average quality of play.

My hope on this Memorial Day is that every one of us thinks about how to raise the quality of our play on behalf of others.

Courage and valor power us through life changing and life threatening moments; humility and humor make the intensely boring bearable; character, however, is revealed on a middle school basketball court, when nobody else sees, but those empowered cherish the memory for the next five decades.

So inspiring, Hal. Thank you for sharing. Cannot help it to be emotional.

Nice. Real nice. For what it is worth, my memory of Steve was a pickup basketball game. I was on a team with Steve’s dad. It was his dad and the little kids against Steve’s older brother Fred and some others. With each point Steve’s dad would hold the ball and announce the score to Fred in an incredulous tone and in a heavy southern accent. This only got Fred more pissed off and rattled. It was my first lesson in psyching out your opponent.

I never hooked up with Steve after HS. He was in a different circle of friends. He had his demons (didn’t we all). What strikes me now and then about his death is its permanence. We grow to middle age while he remains frozen in 1996. That is the tragedy.