The Defender: Steve Voight and Memorial Day

The dynamic range of defense and the time lens of memory.

I’ve edited and recycled this piece a few times over the last decade, including an initial post here three years ago. For the last twnety Memorial Days I have thought of my middle and high school classmate Steve Voigt, Navy Seal Team 8, killed in action on October 25, 1996. In the next year he will be gone as long as his bright life, and it is imperative to retell the stories, with the benefit of time clarity, viewed through a long lens of time, to maintain and honor memory.

This year’s perspective started at Princeton Reunions, filling the front end of Memorial Day weekend as it has the last decade. I stopped at George Segal’s “Binding of Isaac,” one of my favorite spots on campus because of some oblique shared history. Originally commissioned as a memorial to the students killed at Kent State in May 1970, it was returned to Segal for being too raw and emotional. Princeton acquired it as part of the Putnam collection where it now sits between the chapel and the library — securely straddling the space between science and faith. I learned this story from my first Princeton mentor, shortly after the art and I arrived on campus within a few months of each other.

A good friend used to tell me “Good art makes you very uncomfortable.” That has been my 40+ year relationship with “Binding of Isaac” — where Isaac is shown as a college-aged man, on his knees seeking understanding and not prone or face down like a ritual sacrifice. The metaphor of a parent sacrificing a child, whether an allusion to the divisive student-parent gap that fueled Vietnam War protests (read Chrissie Hynde’s “Reckless” for a superb first hand account of that time), or a parent acting out of blind faith, is troubling for me. Why doesn’t Abraham defend Issac? One of my preferred interpretations is that the Biblical story is meant not as a test of faith, but of courage to enact and defend change — as human, often child, sacrifices were a social norm in other tribes of the time.

This notion of “defender” bookends my Memorial Day weekend. En route to Princeton, I take out my CD of Princeton Band songs, with the pomp and circumstance our former radio station program manger would use initiate winter break by unearthing the promotional copy of Springsteen’s “Santa Claus Is Comin’ To Town.” The CD is full of rah-rah, alma mater, football cheers, and marching songs, but my favorite is “The Orange and the Black,” a slow, hymn-like song ostensibly about school colors. The first verse ends with “The tiger stands defender of the orange and the black,” a phrase that I have always taken to implore defense of more than the end zone. It is about identity, ethics, and being part of the much larger Princeton family, celebrated 25,000 strong every Reunions weekend.

Memorial Day commemorates and celebrates the defenders of the red, white, and blue. Not just our country and our flag, but our way of life, our standing in the world, our identity as the land of the free with the homes of the brave on forward Army bases and Navy aircraft carriers.

Unlike a doctor, nurse, or serviceman, I’ve had very few situations in which someone’s life depended up on me and the careful execution of my role. The severity of failure never registered with me as an engineer, until 1991 when I was asked to literally hack a device driver for the US Air Force at the outset of the first Gulf War. Pilots’ lives depended upon my ability to make a Sun workstation talk to an aging TEAC floppy drive with flight logistics data. Contributions to the Gulf War segment of Sentinel Byte, made Woodrow Wilson’s call to “the nation’s service” more clear, and somewhat more personal, but still 10,000 abstract miles away. Leaving technology for healthcare in 2013, and now returning to the world of algorithms and computation, I find myself involved in more projects where the outcomes impact lives. We play a long game, with the opportunity to turn off the Zoom call or revisit the code when we hit a point of frustration. I’ve become acutely aware of this privilege, and its dichotomy with the daily lives of our men and women in uniform.

One fall, decades ago, a new kid named Steve Voigt showed up in our middle school classes. He had moved from the South and everyone remarked on his gentle accent and more gentle manners. He was a remarkably good kid — good at soccer and basketball and socializing — and post high school graduation enlisted in the Navy.

His courage, mental and physical strength and fortitude were ingredients that made him a member of Seal Team Eight. Serving on the aircraft carrier Enterprise in the Persian Gulf and Indian Ocean, during the first Gulf War and before the tensions of 9/11, his service was alternately intensely boring and life changing.

He wrote in a letter to his sister in 1996:

Breakfast: Forty-five minute wait in line. Every meal is the same. Standing in line sweating. That’s OK, though. There are people in my country who neither know or care that their freedom is being protected at this very moment. That too is OK, because I do know. I’m doing it.

He concludes:

I understand freedom and the sacrifices that have to be made for freedom to be achieved. The life we live at the cost of our military members cannot have a price put on it. If you saw our paychecks, you would understand.

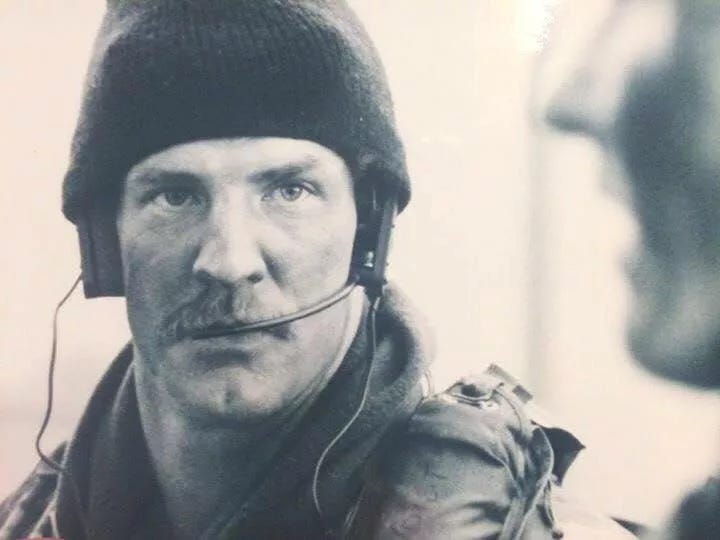

Steve’s entire letter is found at the link, also the source of what I believe to be that last photo of him (above).

He was killed in a search and rescue mission two days later, something I didn’t find out until four years later at a class reunion, and in the 20 years since more details about his service, his commendation and that last letter to his sister have been made public. Steve was, and still is, the only person I know killed in active military service.

Steve’s Navy and Marine Corps Commendation Medal Citation calls out “his ability to motivate his teammates.” While he was an outstanding athlete, he was also a great teammate to the awkward, incredibly poorly coordinated kid on the middle school recreation basketball team (me), and I had the honor of experiencing what would become his outstanding call to personal leadership when I was still a tween. He encouraged me to be better, without picking on me for lowering the average quality of play.

Courage and valor power us through life changing and life threatening moments; humility and humor make the intensely boring bearable; character, however, is revealed when nobody else sees, but those empowered cherish the memory for the next five decades.

This Memorial Day please honor the defenders, those who demonstrated the best of character for all of us, and consider how we collectively identify and seek to defend that which we hold dear.

thx for sharing your story about your classmate.

I don't how it was then, but these days only 1 out of 6 applicants to the SEALS makes it through BUD/S school, so what he did was impressive.

you're also reminding me the time in the early 80's a summer project was getting a PDP/11 to talk to a Z80, and having had to learn both Z80 and PDP/11 assembler language so I could talk to the ports & chips (this was healthcare not defense related).