(Under) Estimated Prophet

Bob Weir was the rhythm guitarist of so many facets of our lives

My Grateful Dead experiences were truly a long, strange trip. Limited to the songs played on AOR FM radio in the mid-1970s, their concert at Englishtown Raceway in 1977 put them on my family’s map. Englishtown is politician’s stone’s throw from Freehold, and the mainstream press predictions of 100,000 hippies showing up created the threat of a tie-dyed menace that proved completely false; it was a peaceful, deep show that featured “Truckin” coming off the musical bench and a crowd that may have topped 175,000. But that positioning of the Dead and their fans as “other” created a tension in middle-class Freehold. I didn’t realize how many of my (then freshman) high school classmates were Deadheads and reveled at that show; just before high school graduation the Dead were musical guests on Saturday Night Live (April 1980) and performed “Alabama Getaway” that was my practical introduction to them as a live act.

Another three years would pass before my college roommate Tom (a long-time Deadhead who once finished a take-home exam early and let me hand it in for him so he could see the Dead at Red Rocks) played Terrapin Station for me — “Estimated Prophet” was the hook with its 7/4 time signature, crying wah and even more exhorted chorus. I drew and colored an envelope for the Fare Thee Well ticket lottery, and finally saw Phil and Friends, Oteil and Friends, and Dead and Company in the past five years to complete my induction into Dead followership.

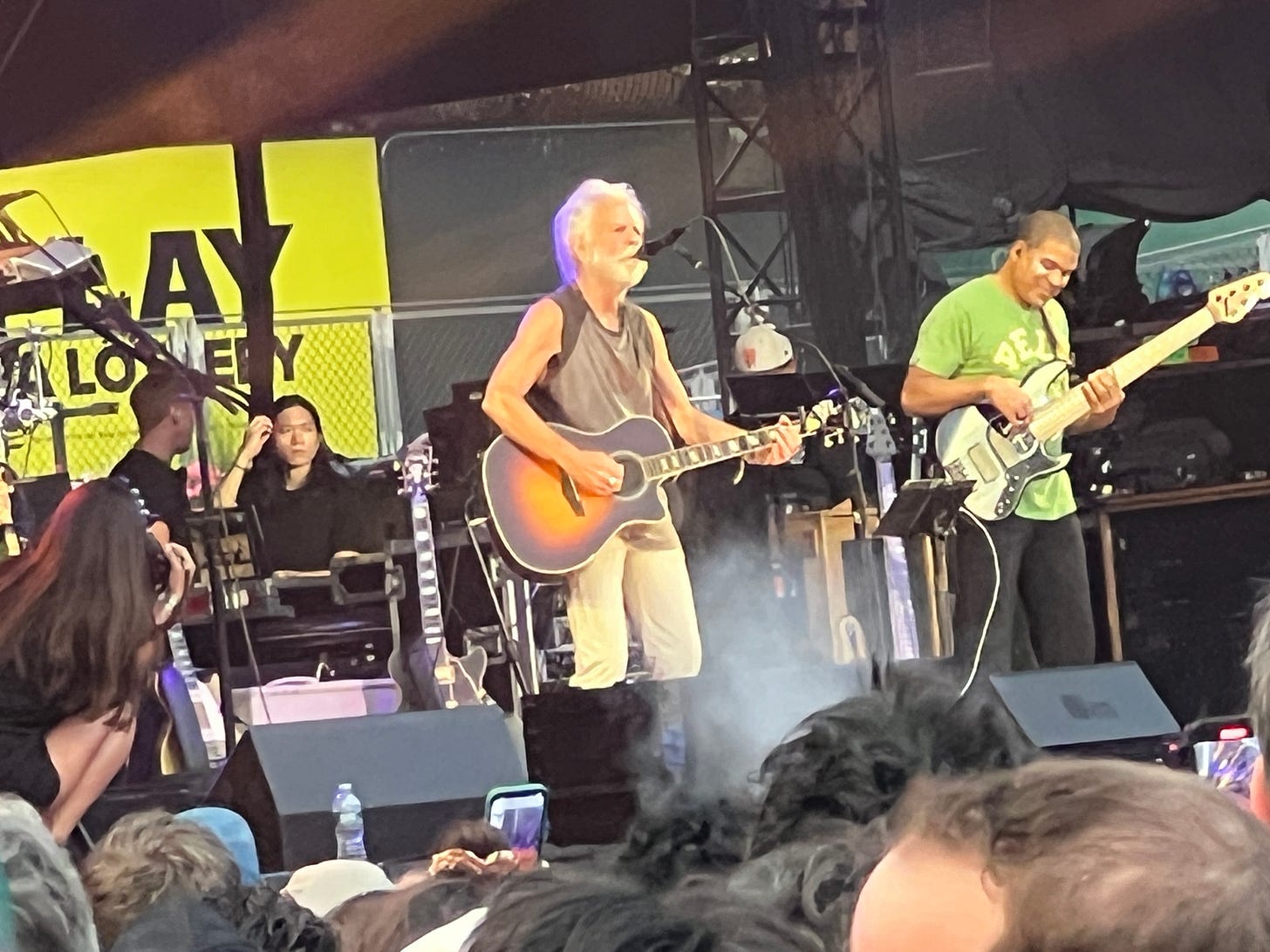

Seeing Bob Weir on stage in Philadelphia, powering through “Estimated Prophet,” “Dark Star” and “Eyes of the World” was magic. It will remain one of my most powerful musical memories, from the intense heat on the field to the people spinning their way through the jams to Weir’s vocals calling to that “prophet on the burning shore” in all 60,000 present.

So I am far from a long-time Deadhead, and even further from an authority on their music and legacy, so Bob Weir’s passing hit me unusually hard. Seeing his legacy reflected by other musicians, and considering his body of work, I think we have witnessed one of the stanchions of modern long-term musical history. Just as we continue to listen to Mozart, Beethoven, and Brahms, hundreds of years after their passing, to study their composition and structure, we will study, perform, and celebrate Bob Weir’s musical legacy for the next five centuries.

Much of our vernacular comes from his lyrics including “long, strange trip” and a midwestern city’s population of dogs named Cassidy.

He likely spent more aggregate time on stage, sharing his inner soul with the audience, than any other musician.

You sense the depth and breadth of the community, the profound respect and raw talent he shared within the comments immediately after his death: Billy Strings called him a “wrangler of the stars.” Trey Anastasio said he was “allergic to compliments.” Memes of him working out and focusing on his health were as rampant as Covid itself, and we all thought he was immortal and eternal. Despite war, disease, inflation, artificial intelligence and electronic music, Bob Weir just kept playing rhythm guitar and writing songs.

Shortly after the release of “Amadeus,” one of my co-workers remarked that if Mozart was alive today, he’d be a hacker — challenging authority, flaunting creativity, making the commons more valuable for all to enjoy. Bob Weir hacked our ability to feel and enjoy music — connecting us, powering us, and forcing us to allocate parts of our minds to new ideas, rhythms and words.

Weir’s amplification went beyond Jerry Garcia: Phish’s Trey Anastasio and pop artist John Mayer join Dead & Co; he brought jazz fusion musicians such as Alphonso Johnson from Weather Report into Bobby and The Midnites, and he continually pulled from every genre.

As the“other one” to Jerry he never played lead, always rhythm guitar. The Dead had a four piece rhythm section with two drummers, Phil Lesh on bass and Bob on rhythm guitar. On the surface that line up with keyboards should have been overly busy, but Bob created room for keys and lead guitar to lift and soar. Shunning simple bar chords of 1970s classic rock, he picked careful arpeggios, accents, and created space for the beats to fall. Bob Weir laid tracks to guide the songs home, using the drums to set the tempo and his rhythm guitar to open things up. Every song is a master class in setting the right notes in the right places.

YouTuber MicksPicks disassembles that 1980 SNL performance, isolating Bob Weir so you can hear every facet of his creativity and how he made “Alabama Getaway” feel as fast and escapist as its title:

When interviewed about my favorite song “Estimated Prophet,” Weir didn’t revert back to Ezekiel and biblical references about fiery chariots; for him it was “about some guy raging in the lot.” That, for me, is the essence of “standing in a shaft of light,” one of the most-quoted lyrics used in his memory. He saw the holy in everyone, everywhere, and used his music to raise it to the surface.

We lost that prophet of the inclusive power of music.